Deepfakes in Politics: Should You Be Worried?

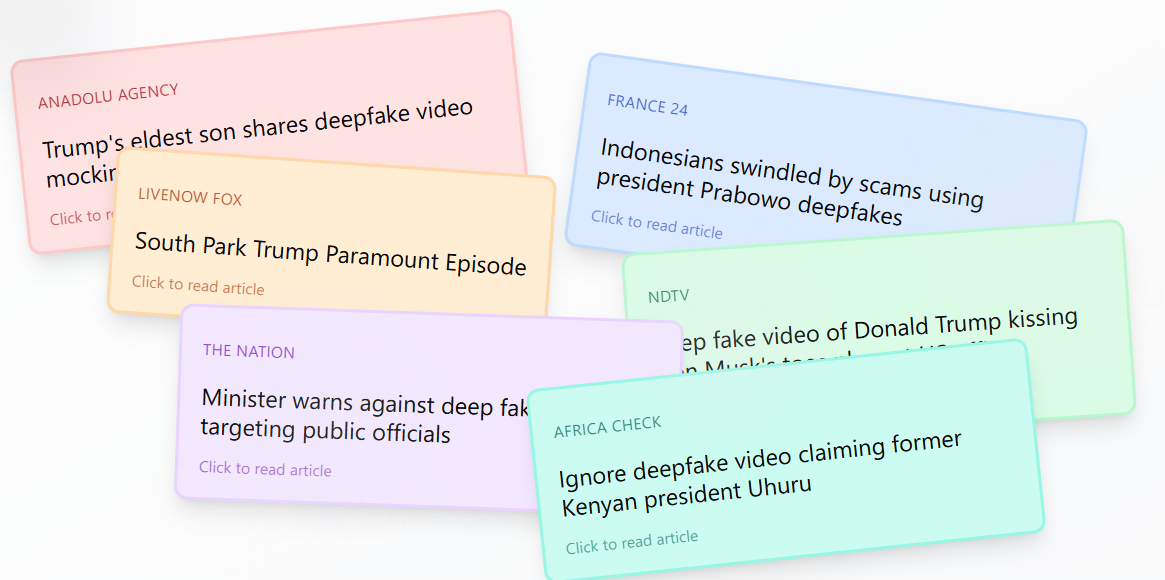

The proliferation of AI-generated images, audio, or video content designed to mimic real individuals has sparked significant legal and ethical debates, particularly in the realm of politics. Across the globe, and increasingly within the African continent, deepfakes are emerging as a potent tool for misinformation, raising serious concerns about their potential to distort public perception, manipulate electoral outcomes, and undermine democratic processes. Besides, many deepfake tools are becoming increasingly sophisticated. This makes it difficult for the average person to discern them from authentic content.

The Legality of Deepfakes: A Case for and Against

Public image is crucial to achieving political ambitions. Goes without say, negative publicity can be damaging, making it imperative for political figures to avoid being misconstrued or defamed in the eyes of the public. However, with the advent of deepfakes, this is harder to achieve as social media users share almost realistic, but misleading photos and videos of politicians online. While free speech rights maintain that such individuals have the right to express opinions and criticize public figures even in a satirical way, liberty to express oneself is not immutable. This begs the question, should one be worried about sharing deepfakes? Can an affected person successfully sue another for sharing deepfakes? where should the balance be struck?

Constitutional Right & Political Satire Vs Character Assassination

From the offset, most courts treat even false political expression as protected under free speech. The constitutions of most democracies, legislations and judicial precedents set across most jurisdictions widen the scope of free speech to include satirical works, parody and incendiary speech As was the case in Hustler v. Falwell-style suits, deep fakes deemed satire or parody typically receive full protection.

However, this right is not absolute and is subject to limitations. When deepfakes are seen to be outrightly defaming another, then they go beyond the realms of protection. When deepfakes are crafted to portray false information about a person, they can constitute a false statement of fact. If such content is published or shared with third parties and causes reputational harm, it satisfies the key elements of defamation: falsity, publication, harm, and fault. In these cases, deepfakes lose protection under free expression laws and may expose the creator or distributor to civil liability.

Furthermore, when it comes to election interference, deepfakes are normally viewed differently and they can be judged harshly. Jurisdictions are already treating deepfakes as a serious threat to election integrity and the entire democratic process. Therefore, depending on the specific laws of certain jurisdictions, anti-deepfakes policies are being enacted with the aim of deterring their malicious use, ensuring transparency, and providing legal recourse for those affected by them.

Legal insight: Deep fakes intended as political satire are generally protected as free speech: restrictions focused only on “knowingly deceptive” deep fakes narrowly targeted at election interference are more legally sustainable, but even those face constitutional scrutiny.

Entertainment Value vs. Deception

In the latest episode of “He Must Go,” Kenyan social media has been graced with deepfake videos of individuals literally taking one on the leg—allegedly inspired by President Ruto’s now-viral “shoot in the leg” directive.

And two distinct approaches have been given to the scenario. His detractors argue that it’s mere entertainment while proponents of the president are worrisome that the trend is inflammatory and deceptive.

|

Anti-Deepfake

This chilling trend illustrates just how recklessly users are propagating a culture of violence by using AI for deception and PR spin |

Striking the balance is the real deal. Many deep fakes are harmless entertainment: comedic parodies of political figures or clever mashups. Under most systems, these are free speech, even if unrealistic or comedic, as long as audiences reasonably understand the creative intent.

Key legal factors to look out for are:

- Context: Clear labeling or obvious satire supports free speech claims.

- Intent: Satirical intent differs legally from intent to defraud or manipulate.

However, when the intent is deemed to be deception, then such deepfakes fail against the threshold of entertainment value.

Hate Speech, Cybercrime & Non‑Consensual Deep Fakes

Deep fakes also raise serious concerns about hate speech and harassment. Legally, these are not protected, and jurisdictions are responding:

- Non-consensual intimate deep fakes—Deepfakes that showcase explicit and pornographic content featuring unwilling individuals—are unequivocally banned in most jurisdictions.

- Hate-oriented deep fakes, such as racist or sexist content targeting protected groups, may be prosecuted under hate speech or incitement laws depending on the country.

Takeaway

From the foregoing, deep fakes in politics fall into three legal zones:

| Use Case | Legal Status |

| Satire/parody | Protected as free speech |

| Defamation or disinformation | Potential liability |

| Hate/cyberbullying or non-consensual content | Disallowed and prosecutable |

Call to Action

Looking for professional legal expertise to help you navigate free speech, labeling obligations, defamation risks, or hate speech concerns around politically generated AI content?

Contact Us for tailored legal advice and compliance support.